Between the stomach and airways, we have sphincters.

These are made to protect us from reflux.

Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease (LPR) is caused by a problem with these sphincters.

I have interviewed Dr. Mark D. Noar to get a deeper insight into this matter.

Dr. Noar is a gastroenterologist who has a deep understanding of reflux causes, diagnosis and treatment options.

This is the first part of the interview. In the following parts, we will talk about diagnosis with pH monitoring, the Stretta procedure, and operations.

Part #1 – The Sphincters & Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease (LPR)

What is the role of the sphincters in LPR?

Dr. Mark Noar: Our bodies have different sphincters that exist to stop reflux.

These sphincters are complex, multifunctional and under independent neurological control by the Vagus and Phrenic nerve nucleus in the brain.

All of them work together and are able to stop reflux.

Imagine the sphincters as backup mechanisms. In a space shuttle, they have backup computers and backup systems in case the main ones fail. Your body has the same thing when it comes to reflux.

Something that is often mentioned in connection with reflux is the lower esophageal sphincter. This is the valve between the stomach and esophagus. What is the involvement of this sphincter in laryngopharyngeal reflux?

The root cause of reflux is a problem with the lower esophageal sphincter, LES for short.

Just like other organs in our bodies, it degenerates slowly over time. That means it opens easier and more frequently than normal. As a result, more reflux has the chance to get into your esophagus and then up into your larynx.

Can you explain in more detail how the lower esophageal sphincter works?

For a long time, people thought the lower esophageal sphincter was a single simple sphincter made up of one muscle layer in the esophagus that keeps the sphincter shut.

However, research has shown that it is not that simple. We now know that there are two sphincters of the LES that work together like players on a team.

The first one is the internal sphincter. You can also call it the intrinsic sphincter.

The second is the external sphincter. It is made up of the muscles of the diaphragm that surround the esophagus.

This is a very important point. It means that people can have problems with different parts of the sphincter. Therefore, a solution that fixes one malfunctioning layer may not fix the actual problem.

Now, there is one thing that both of them have in common: overeating or consuming too much of the wrong foods or drinks causes the sphincters to malfunction. If you overload your stomach, your sphincters have to work hard to keep reflux from happening. If you do that often, your sphincters will get weaker over time and actually degenerate.

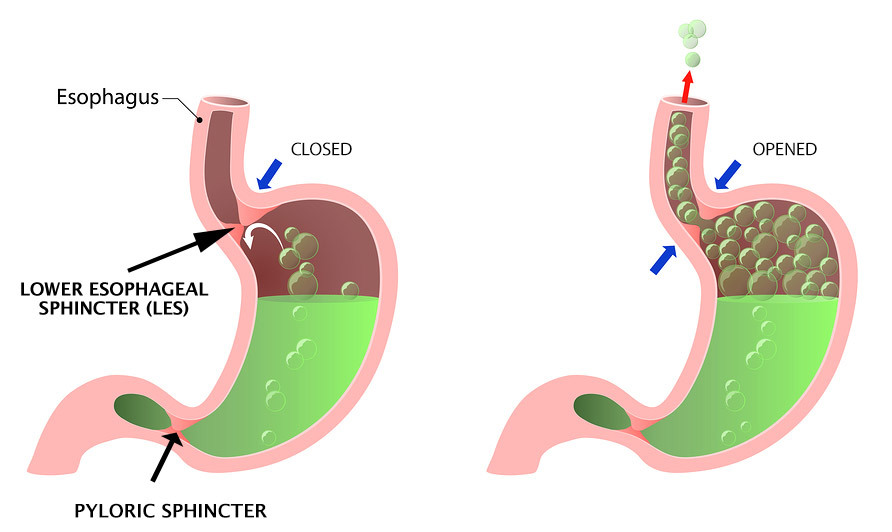

How does reflux happen when you have weakened sphincters?

The weakened sphincter cannot withstand the pressure from the stomach anymore.

You have to understand that the stomach normally builds pressure as it contracts to work properly. To understand that, we have to look at the pyloric sphincter.

The pylorus is the sphincter at the exit of the stomach. Food has to go through it to be further digested. The pyloric sphincter has a very narrow diameter. It never opens more than about 2 or 3 mm. So to pass, your food has to be ground down to millimeter-sized pieces.

Your stomach contracts to press food through the pylorus. But the lower esophageal sphincter has to hold against this pressure. If the LES is too weak, it opens. The result is unchallenged reflux.

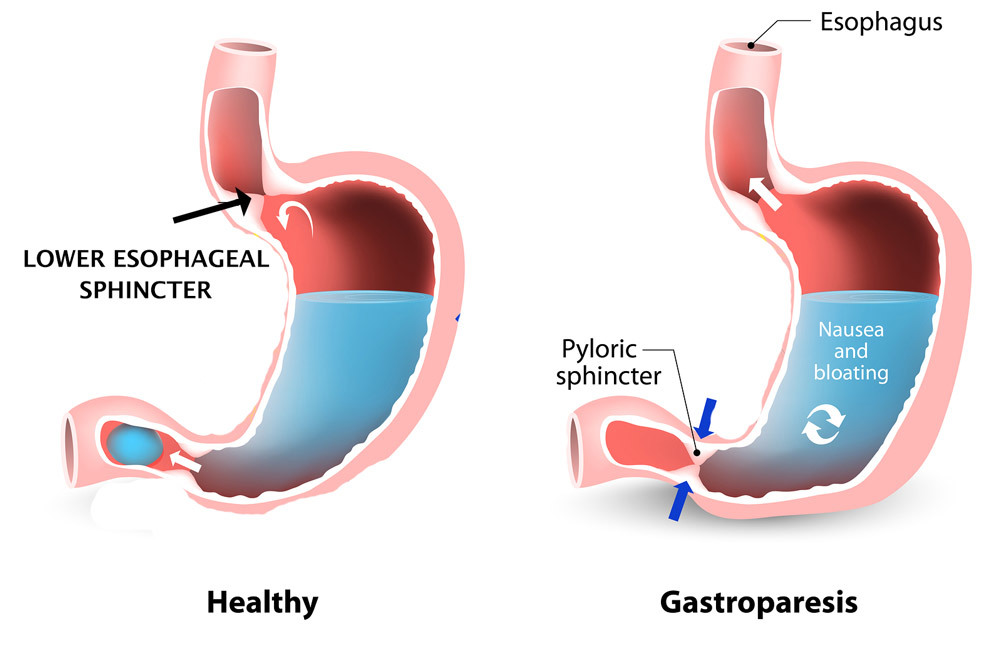

Another factor may be delayed gastric emptying. The medical term for the disease is gastroparesis. In up to 40% of people with reflux, the stomach simply cannot empty itself properly, as the valve that leads to your esophagus opens up all the time. So food gets pushed up into the esophagus instead of into your intestines.

How can we fix it when the sphincters do not work properly?

There are some very important basic measures that you can take. Most important: you should never eat more food than the size of your fist at once.

That is what your stomach is designed to accommodate. To express it more technically: about 750cc volume of food is ok.

If you go to a restaurant, most people are not eating just this handful of food.

That’s why so many people develop reflux: because they are constantly challenging how our digestive system is supposed to work.

What does that mean for treating LPR patients?

Everything needs to be directed towards sphincter preservation.

We begin with basic measures: lifestyle changes and dietary changes are extremely important. You have to change when, how much, and what you eat.

If that doesn’t work, you may try a little medication as a test.

This is done to lower the acid level. We can then see whether your symptoms improve.

If you get well and stay so after your doctor stops the medication, then your sphincter is likely still strong enough.

Your body just needed a break to heal the damage. If you do not get better, then we need to do something to improve the function of your lower esophageal sphincter.

What is a good point in time to consider fixing the lower esophageal sphincter?

The fact is that you can allow your sphincter to continue to degenerate and still feel good. Taking medication is like using a Band-Aid. You can take your Nexium. You can take your different proton-pump inhibitors. Even if it works, your sphincter is going to continue to degenerate.

Eventually, you are going to end up needing to have something done. The more you wait, the harder it is to fix. When we do things like the Stretta procedure, patients who have had a shorter interval of symptoms have the best results.

Patients who have had severe symptoms for the longer periods of time will frequently require either a second Stretta procedure or an additional procedure like a Nissen fundoplication to get all the way better.

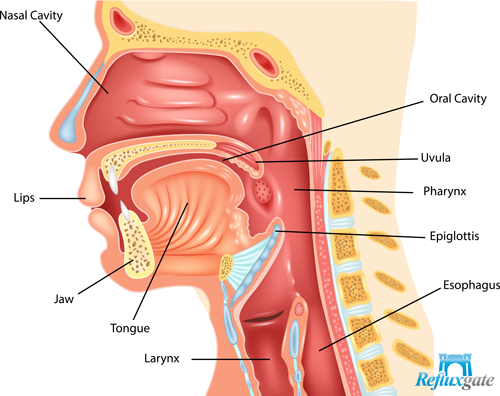

There is also the upper esophageal sphincter. This is the sphincter that sits between the esophagus and larynx. What role does it play in LPR?

The upper esophageal sphincter is usually tighter than the lower esophageal sphincter….so it is harder to open to protect the larynx and airway.

Sometimes it gets worse in LPR patients, and the sphincter becomes reactive and even tighter or spastic to try and guard against continued reflux.

When liquid comes up and tries to get into your throat, the sphincter gets tighter, and your throat closes off. But when it comes up in a gaseous form, it is much harder to block it from coming up completely. Gas is much harder to stop than liquid.

What happens if reflux passes through the upper esophageal sphincter?

If reflux gets past the upper esophageal sphincter, it can go anywhere. This is the start of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease.

It can get into the larynx, nasal passages, Eustachian tubes, ear passages, sinuses, bronchi or the whole throat area in general.

In the laryngopharyngeal type of reflux, it’s all about pepsin. Pepsin comes up in an aerosolized form, which makes it vicious. That’s how it gets into the nose, the ears, and the lungs because it’s not liquid.

Is this common knowledge among physicians?

Reflux, in general, is incompletely understood in the medical community.

This is because much of the newer ideas, supportive literature, and the education that have taken place in the field of reflux over the past 10-15 years have been overlooked or ignored.

If you ask most physicians what causes reflux, almost all of them will say: it’s due to acid.

But this is not correct.

It’s impossible to reflux acid only. You’re going to reflux everything that’s in your stomach. Including pepsin, which causes a lot of the damage in laryngopharyngeal reflux disease.

Can LPR cause chronic inflammation which does not go back to normal after an operation? So that you get into a vicious circle that does not stop – even when the reflux is gone?

Once you shut down laryngopharyngeal reflux, the symptoms of the disease stop, unless you have something else causing the irritation.

There can be multiple reasons for irritation, including reflux, allergies or nerve injury.

Some people truly have allergies, and that creates chronic inflammation.

You have to fix the reflux first and then fix what’s left over.

End of Part #1 of the Interview

The interview with Dr. Mark Noar was packed with useful information.

I have split it into multiple parts to make it easier to digest. The next parts are about LPR diagnosis with Restech pH Monitoring and the Stretta procedure.